Vision

Written by Harold de Haan

His love for stainless steel blossomed when he worked as a welder on an offshore platform. It was there, on that huge weather-beaten structure in the sea, that Ronald A. Westerhuis found his inspiration. Inspiration which led to art. And this art subsequently led to social commitment. “I used to focus on arranging things for myself. Now I want to give back to society.”

Ronald A. Westerhuis, who has a studio in Zwolle and a workshop in Shanghai, is driven by restlessness. “I’ve always felt restless. When I was seventeen I bought an Interrail card and travelled around Europe for a month. In Venice I met a couple who invited me to their home in the USA. That was the beginning of a seven-year trip around the world. I travelled through the USA, Aruba, Mexico and Asia. School didn’t interest me, I wanted to see the world. And I never stayed long in one place, I always wanted to move on. I felt like I didn’t belong anywhere. And I still feel that way.”

He finally ended up working as a welder on oil rigs around the world, some of which stood up to three hundred metres high and housed as many as one thousand crew: the harsh environment of the offshore industry. “It was the most honest place on earth. Nothing was fake there.” He worked on a rota basis of two weeks on and two weeks off (during which he usually felt rather bored).

His love for stainless steel

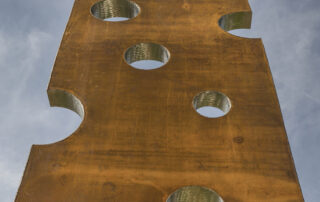

“I was very much impressed by the weathered offshore structures of stainless steel. Stainless steel is a fascinating material. It’s cold and hard but also has a timeless sensitivity. I wanted to do something with that, so I rented a workshop and simply started on my first project.”

This eventually led to an exhibition in a synagogue in Dalfsen. “I rang my employer the day after, on Monday, and quit my job. He was not amused and said I was throwing away my future. I didn’t see it that way. I was doing what I loved to do and now had the opportunity to explore my inner self, to discover my own identity.”

This journey of discovery is what still drives Westerhuis today. What has changed, however, is that he now no longer works alone but is assisted by his team. “Raoul is my right-hand man. He’s twenty years younger than me and has a very keen eye. I learn from him, just like he learns from me. He came here nine years ago as a child from a problem family, following an apprenticeship scheme, and he has never left.”

Westerhuis sees much of himself in Raoul. “I’ve also had ex-criminals, children from broken families and street kids working here. They were all very loyal to me. By teaching them a trade and helping them to develop themselves I’m able to give something back to society. In my first years as an artist I used to focus on arranging things for myself. Now it’s time for me to help others. My team is my family.”

My team is my family

There is no place for hierarchy at the workshop. “Together, we discuss the sculptures. I’m not the boss, but I am the one who does all the sketches. I outline things on the materials in the workshop, and I create sketches while flying to or from Shanghai. I draw inspiration from myself and from art I’ve seen at galleries or fairs. I’m able to tap into all these images stored in my mind. Ultimately, all this blends into my own visual language.”

This visual language is characterized by round shapes and large sculptures because size matters to Westerhuis. “I believe in the power of landmarks.” A good example is the project he is currently working on: a sculpture commissioned for the Hardanger Fjord in Norway which will be no less than 300 m high! Furthermore, he dreams of making a sculpture that will be as large as, and have the same impact as, the Eiffel Tower one day. “In essence, I want my work to exude positive energy. A sculpture and its site should mutually reinforce each other and form one integrated unit.” In this sense, a new reality is created which actually contributes something to the site. “This may also be economically, as will be the case in the Hardanger Fiord. It will draw day trippers and tourists, and create employment. This kind of art is therefore not elitist but actively participates in society.”

Westerhuis is aware of the power of artwork. With sculptures around the world, at art galleries and in private collections such as that of Prince Albert of Monaco, and collaborations with architects such as Daniel Libeskind, Westerhuis not only shows that he is able to create appealing and award-winning sculptures, but also that he belongs to ‘the new generation of artists’, as pointed out by Ralph Keuning, Director of Museum De Fundatie. “Conscious artistry involves more than just creating art,” lectures Westerhuis. “You should also be a businessman, which means you need to make sure you get noticed as an artist, come out of your studio and engage in networking. You are part of society and should therefore interact with society.”

I believe in the power of landmarks

In the Netherlands, this involves a no-nonsense approach and conforming to the crowd. In China, however, self-taught artist Westerhuis stands out from the crowd and is idolized. His sculptures can be found in various public spaces in Shanghai, and dignitaries think the world of him. “I saw much of my own visual language reflected in Chinese art and culture. China is a difficult market to penetrate – and as a Westerner you need to throw all your preconceptions overboard – but it’s also a market with unprecedented opportunities. It was my longing for the unknown that brought me there. Yes, that old restlessness again, but also a desire for personal growth. So, basically, I’m pursuing my desire for personal growth rather than creating art. I pursue that desire by making sculptures together with my team.”

His studio in Zwolle reverberates with the typical sounds associated with working with stainless steel. The team is working on a sculpture for the Lowlands Festival, a popular three-day music and art festival. Raoul is there of course. Music is playing. The coffee is being made. Westerhuis: “I lead a rather spartan life. I get up at five o’ clock, make a smoothie with carrots, ginger and spinach, and then often take an hour-long swim before I go to my studio.” He likes a drink but doesn’t do drugs. “In that respect I’m a rather dull and boring artist. I also hardly ever go to a pub.”

Incidentally, he prefers not to call himself an artist, he hurries to say. “Anyone can call themselves an artist. I think ‘artist’ is a title you should earn. I make sculptures because I feel the need to do so.” Westerhuis describes himself as a creative mind. “By doing so, I keep all options open, just in case I should want to do something else in the future.” In other words, he doesn’t want to be pigeonholed because he needs to be able to express his restless creative energy freely. “You should not confuse this restlessness with stress and agitation. In 2005, I lived in jetlag mode. I regularly flew to Shanghai, and I never took a break, everything had to be bigger and stronger and go faster. Eventually, I got a burn-out. I stayed at my mother’s home and my summerhouse on the river IJssel to get some much needed rest. Through therapy and a step-by-step recovery programme I finally regained my strength. I have been in control of my life ever since, and I now know how to keep balanced.”

“I count myself lucky. Each day I can do the things I like together with my fantastic team and dear friends around me. I still gain new insights into myself when working on a sculpture, and I feel privileged that I’m able to provide others with opportunities. I also have plenty of ideas for the future. I’d like to transform this workshop in Zwolle into a place where young people can learn traditional crafts. And I have this dream of converting an old oil tanker into an international centre where artists can work together and exhibit their work, sailing it to different parts of the world. Helping others is what ultimately counts for me.”